Prof. Alisa Bierria was interviewed by the Black Agenda Report about mutual aid as an organizing practice. Excerpt below:

How does this work fit into the broader struggle for change you are working on? How does it mobilize for change rather than merely being a “band aid” on a harmful system?

I was a member of the #FreeBresha participatory defense campaign to free Bresha Meadows, a Black girl who was only 14 years old when she fatally shot her physically and sexually abusive father. Bresha attempted to get help from multiple authorities before the shooting, all of whom failed to help her. So, she acted on her own to defend her life. In a recent interview, Bresha said it never occurred to her that she would go to jail. She thought it would be obvious that she was acting in self-defense, and everyone would agree.

It’s remarkable and powerful to me that Bresha thought it would be obvious that jailing her for saving her life would be out of the question. Because the principle of punishment occupies so much of our instinct here in the U.S., this is, disturbingly, incorrect. I think “reason” is a landscape on which mutual aid can have a profound impact. Bresha’s story reveals that mutual aid in the form of defense campaigns has to be about more than decarceration and more than ensuring material needs are met; mutual aid is about creating a radical shift in what we think is reasonable to expect. In the participatory defense campaigns I’ve worked on, we’ve used a number of strategies — media advocacy, art, political education, research, foregrounding survivors’ narratives of their own lives and choices — to make a case that incarcerating survivors for navigating conditions of violence is actually horrifying, doing so should be out of the question, and freeing incarcerated survivors is an obvious moral imperative. Mutual aid has the potential to transform “common sense.”

…

Do you think mutual aid work has any special or particular role in the current conditions/crises?

In light of the pandemic, we have seen an extraordinary emergence of mutual aid strategies around the world. These efforts provide opportunities for people to support each other and be provided with what they need, build community networks, and participate in political education, all key components of mutual aid praxis. They also shine a light on life-saving mutual aid work that existed before the pandemic. For example, organizations like the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP) have been able to respond quickly to the Covid-19 crisis in prisons because, through decades of supporting, learning from, and building networks with people across prison walls, their members have built an infrastructure of relationships and skills that challenge the health crisis of prison itself. Mutual aid practices address immediate and ongoing needs while equipping us to recognize and respond to future needs.

But I’m also interested in how people have used the crisis to ask important questions about capitalism. For example, if states can release thousands of people from jails to avoid worsening a pandemic, do we even need jails at all? Does the current rent-strike raise questions about whether rent is necessary to have housing? Does the suspension of federal student loan payments suggest that it’s within our reach to permanently cancel multiple forms of debt? Also, the way the pandemic has shone a light on the ease in which the U.S. treats immigrants, poor people and people without stable and safe housing, incarcerated people in all forms of lock-up, elders and disabled people, Black women, etc. as essentially disposable may not be surprising to many of us, but is always devastating. Under Covid-19, we’ve learned more about vulnerability, collective capacity, and how things that seem permanent (good or bad) can actually become quickly unsettled. I’m hoping we can use those insights to take a fresh look at things like Universal Basic Income, prison abolition, profound racism in the healthcare industry, disability justice, and safe and accessible housing.

—

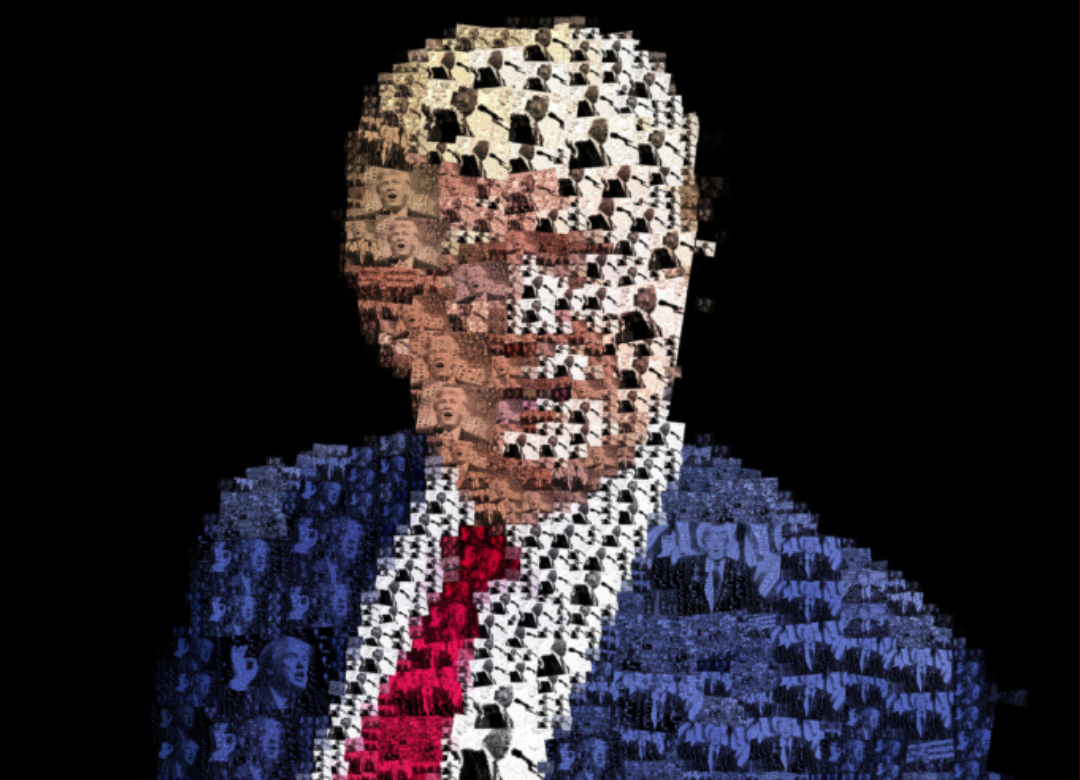

Art above by Josh MacPhee