The UCR Ethnic Studies department has faced a number of challenges this year in addressing COVID-19, meeting student needs in the midst of instability and financial precarity, and the impact of racism on our students brought to light by the mass movement in support of Black Lives. We have issued a statement in support of Graduate Students organizing for a living wage and a statement supporting UCR Undergraduate Students Demands to the UCR Administration. We have also begun our community engagement programs which bring together faculty, graduate students, undergraduate students and community members to address the pressing issues of our time.

Despite these challenging times, UCR Ethnic Studies faculty have found creative ways to teach during the campus shut-down. They have also produced path-breaking scholarship while engaged in diverse community organizing projects. Graduate students have won numerous awards this year. They have taken part in a variety of social justice initiatives while pursuing innovative scholarship. UCR Ethnic studies undergraduates have organized a number of successful projects to improve the well-being of the Riverside community and campus life.

Major accomplishments are below. Read the newsletter for our full report!

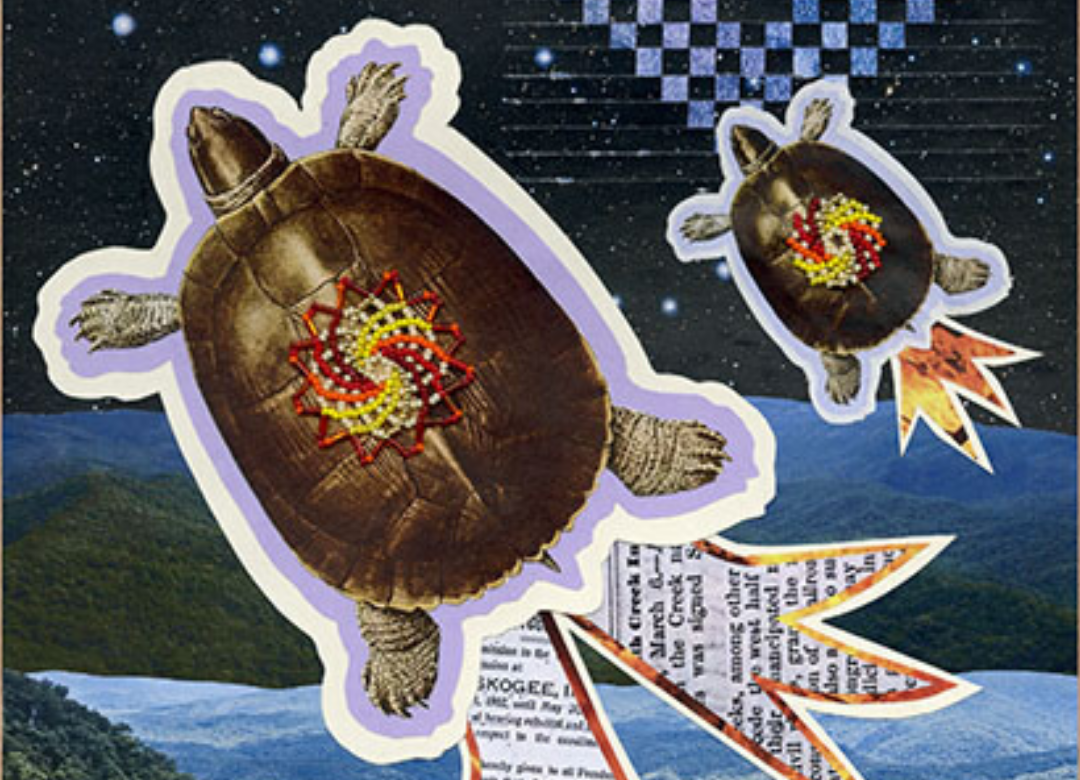

Image above from the cover of Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Black Racism, featuring art by Kimberly Robertson and Jenell Navarro, “Postcard from an Otherwise World”

Faculty News

Wesley Leonard and Adrián Félix were promoted to Associate Professor with tenure.

Andrea Smith published Unreconciled: From Racial Reconciliation to Racial Justice in Christian Evangelicalism (Duke) and Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Black Racism (co-edited with Tiffany Lethabo King and Jenell Navarro, Duke). Otherwise Worlds emerged from the Otherwise Worlds Conference at UCR Riverside.

Jennifer Najera published an OpEd in the Los Angeles Times this Fall, “My Grandpa Was a Dreamer Who Crossed the Rio Grande.” This Spring she was selected as an “Outstanding Faculty Mentor” for the University Honors Program.

Edward Chang was awarded the Order of Civil Merit, Magnolia Medal by the Republic of Korea.

Alisa Bierria published “Battering Court System: A Structural Critique of ‘Failure to Protect'” in The Politicization of Safety: Critical Perspectives on Domestic Violence Responses (co-authored with Colby Lenz, NYU Press).

Emily Hue published “Fifteen Years after Buddha Is Hiding: Gesturing Toward the Future in Critical Refugee Studies” in Women’s Studies Quarterly

Wesley Leonard was awarded a $1 million Mellon Grant to support Indigenous Studies at UC Riverside.

More faculty updates here.

Graduate Student News:

Jennifer Martinez won the Outstanding Teaching Assistant award for AY 2019-2020.

Frank Perez and Lawrence Lan were the inaugural recipients of the department’s Edna Bonacich Award for their community engaged research.

Cinthya Martinez was selected for the GRMP next year to further develop her project, “Freedom is a Place: Abolitionist Possibilities in Migrant Women’s Refusals.”

Beth Kopacz won a dissertation fellowship from the American Association of University Women to complete her dissertation, “Molecular Longing: Adopted Koreans and the Navigation of Absence through DNA.”

Jalondra Davis (Ph.D. ’17) was awarded a UC President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship at UC San Diego.

Iris Blake’s publication “The Echo as Decolonial Gesture” will be published in Sound Acts, a special issue of the journal Performance Matters. She will be a UC President’s Postdoctoral Fellow at UCLA starting in September.

Ray Pineda’s “Authoritative Voice and Mujerista Mentorship of Dissonant DJs Queering Cumbia Sonidera” will appear in Chicana/Latina Studies: The Journal of Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social.

MT Vallarta’s “Toward a Filipinx Method: Queer of Color Critique and QTGNC Mobilization in Mark Aguhar’s Poetics” will be published with The Velvet Light Trap.

Brian Stephens, “Prissy’s Quittin’ Time: The Black Camp Aesthetics of Kara Walker” appears in Open Cultural Studies.

Undergraduate Student Announcements:

Vivienne Lu won the Wilmer and Velma Johnson Ethnic Studies Undergraduate Award. She also won the Sumi Harada Award for graduating joint major with highest GPA.

Violetta Price and Alana Pitman won the Dosan Ahn Chang-Ho Award for the Junior major with the best GPA.

Christina Canales won the Maurice Jackson award for the graduating major with the highest GPA.

Jazmin Jefferson Faten won the Ernesto Galarza Award in recognition of community service.

Joaquin Malta won the Katherine Saubel award for promotion of cultural awareness.

Kyra Byers and Vivienne Lu won the Barnett Grier Award for promoting ethnic awareness.

Maribel Cruz and Sofia Rivas won the Sister Rosa Marta Zarate Award for community service.

More student updates here.